Anal Fistula is an abnormal tunnel-like connection between the inside of the anal canal or rectum and the skin near the anus. It usually develops after an infection in one of the small anal glands leads to an abscess (a collection of pus). When the abscess drains—either on its own or after surgical treatment—a persistent tract may remain, creating the fistula.

1. Causes

- Infected Anal Glands – The most common cause, often starting as an anal abscess.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) – Especially Crohn’s disease.

- Tuberculosis, Radiation, or Cancer – Rare causes.

- Trauma or Surgery – Can occasionally lead to fistula formation.

2. Symptoms

- Persistent Discharge – Pus or blood from an opening near the anus.

- Pain and Swelling – Especially during bowel movements or when sitting.

- Recurring Abscesses – Repeated episodes of infection and swelling.

- Irritation – Skin itching or redness around the opening.

3. Types

- Simple Fistula – A single, straight tract.

- Complex Fistula – Multiple tracts or those involving more of the sphincter muscles.

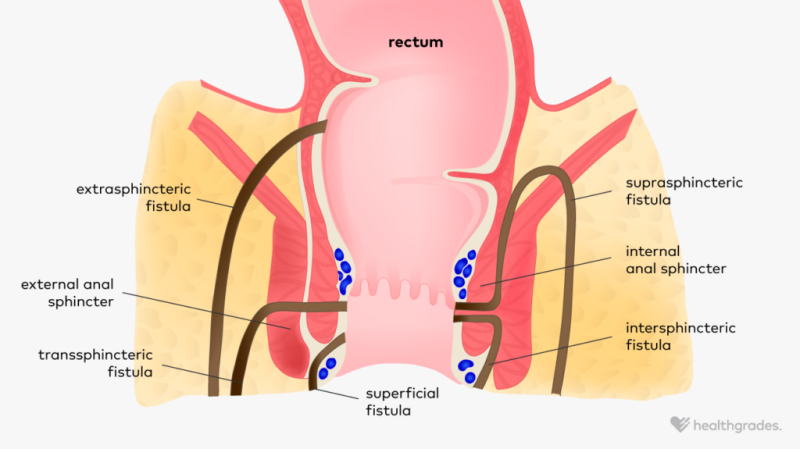

- Classified based on their relation to anal sphincters:

- Intersphincteric

- Transsphincteric

- Suprasphincteric

- Extrasphincteric

4. Diagnosis

- Physical Examination – Doctor inspects and probes the tract.

- Imaging – MRI or endoanal ultrasound to map the fistula pathway.

- Examination Under Anesthesia (EUA) – Sometimes needed for accurate mapping.

5. Treatment

An anal fistula rarely heals without surgery.

- Fistulotomy – Opening and flattening the tract to heal from inside out (for simple fistulas).

- Seton Placement – A surgical thread to drain infection and protect sphincter muscle.

- Advancement Flap or LIFT Procedure – For complex cases to avoid incontinence.

- Fibrin Glue / Plugs – Minimally invasive options, though less effective.

6. Risks of Untreated Fistula

- Chronic infection and abscesses.

- Spread of infection to deeper tissues.

- Risk of sphincter damage if infection worsens.